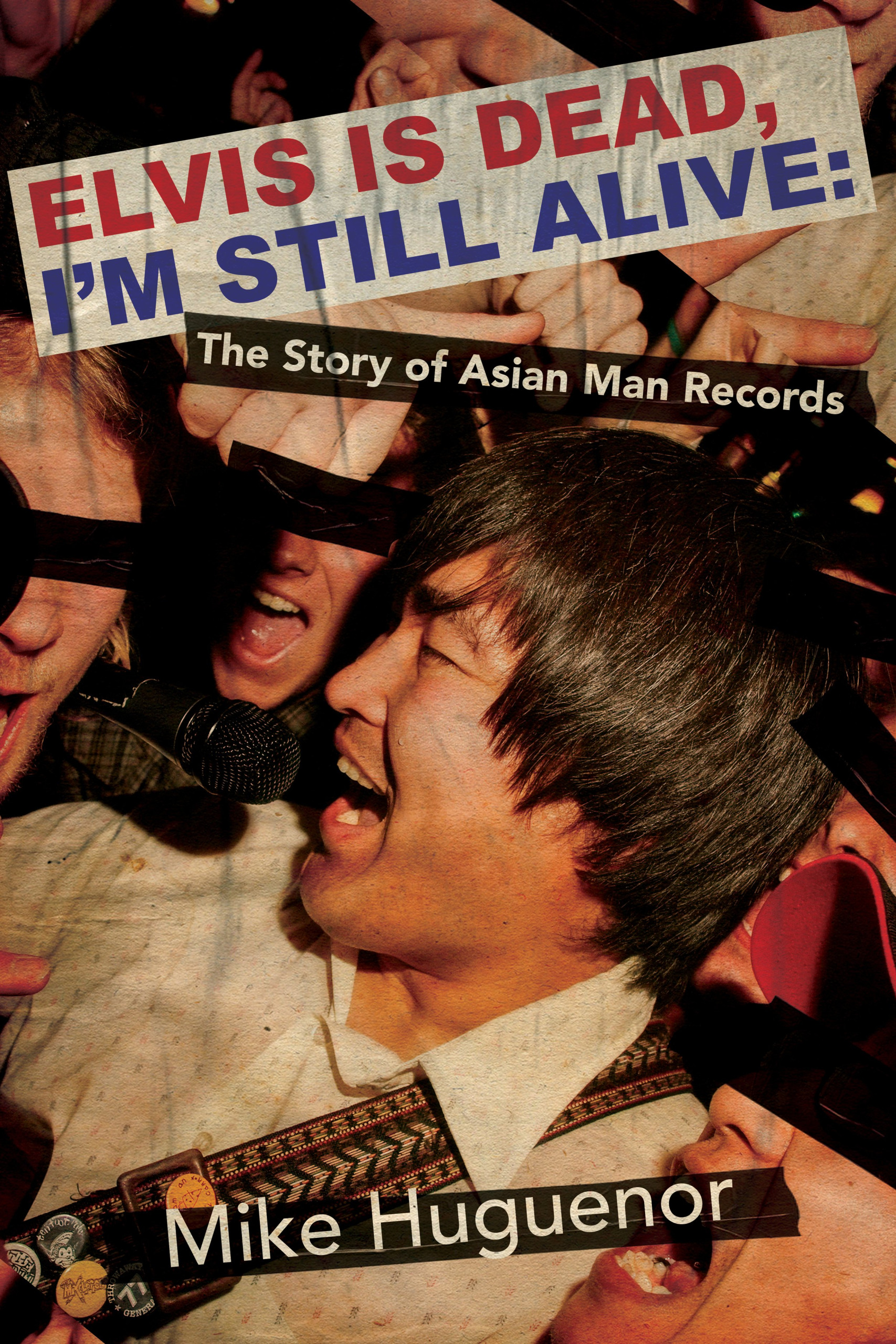

Now Reading: Read an excerpt of new Asian Man Records book ‘Elvis Is Dead’ by Mike Huguenor

-

01

Read an excerpt of new Asian Man Records book ‘Elvis Is Dead’ by Mike Huguenor

Read an excerpt of new Asian Man Records book ‘Elvis Is Dead’ by Mike Huguenor

Mike Huguenor of Shinobu, Hard Girls, and Jeff Rosenstock’s band (and who’s also a solo artist) is gearing up to publish his first book, ‘Elvis Is Dead, I’m Still Alive,’ which tells the story of Mike Park’s iconic independent label Asian Man Records. The label has been home to Alkaline Trio, Less Than Jake, Joyce Manor, Big D and the Kids Table, The Lawrence Arms, Dowsing, Spraynard, and so many other great punk, indie, emo, and ska bands over the years, and it continues to put out great records, year after year.

Huguenor conducted over 100 hours worth of interviews with over 100 people for the book and “has seen the label from inside and out,” according to the book synopsis. Mike Park himself said, “I spent many hours going on walks with Mr Huguenor telling my story. He even convinced my mom to do an interview.”

‘Elvis Is Dead, I’m Still Alive’ comes out May 19, 2026 via Clash Books, home of ‘In Defense of Ska’ (pre-order), and we’re now debuting an excerpt about how AMR got its first employees.

**

Tony Rodgers didn’t have his own radio show, but listeners of 90.5 KSJS—San Jose State University’s radio station—could hear him weekly on his friend Jeremiah’s show “Local Motion.”

“I’d like to say it was my show, but it was really his,” Rodgers says.

At SJSU, Rodgers was studying to become an elementary school teacher, but he found he enjoyed spinning punk records more. One day in 1996, he and the actual host of “Local Motion” were on their way to the weekly KSJS station meeting when they bumped into a tall Korean American guy they immediately recognized as the sax player from Skankin’ Pickle. As an undergraduate at San Jose State, Rodgers had been at the Rumble in the Ballroom, Mike Park’s second-to-last show with the band.

The DJs asked Park what he was doing on campus. He told them he was headed to the radio station. He wanted to become a KSJS DJ, too.

“So, we walked him in there. That’s how we got to know each other,” Rodgers says.

In the halls of San Jose State, Park told his new friends that he had split with both Pickle and Dill and started his own label. Would they, he wondered, maybe be interested in helping out in the garage?

“We were like, ‘Yeah, absolutely, that’d be fun,’” Rodgers recalls.

Park never followed through on his plan to DJ on KSJS, but from this one brief conversation in the halls of San Jose State, Asian Man picked up its first full-time employee.

For a few months, both hosts of Local Motion came by the Asian Man garage on a voluntary, weekly basis. But as the label picked up steam, it became clear there was enough work for a full-time employee. Before long, Park offered Rodgers a permanent role packing mail order.

Naturally a morning person, Rodgers showed up at 7am the next morning, knocking on the garage door until he was let in.

“I don’t know how happy Mike’s mom was with that,” he says, laughing at the memory.

But by 7am, there were already plenty of orders to fill. As the day went on, crates of mail would arrive from the post office, letters with orders clipped from zines or the catalog included in each Asian Man album.

That was in 1997. By 1998, when the label was in full swing, Rodgers says the volume of daily mail order quadrupled.

“It was unreal. It was outrageous,” he says. “There were stacks of mail every day. I’d be busy all day long doing mail order. And it wasn’t just orders. A lot of these kids were writing letters to us. It was almost like having penpals. It was really fun. With every order, I wanted that customer to understand that we were punks just like them. We weren’t just some corporation taking their money.”

*

Miya Osaki came to Asian Man as an employee around this time, though the first time she asked Park if she could work for him, he said no.

“He didn’t have any work for me,” she recalls. “Tony was there.”

Osaki had grown up in LA and come to Santa Cruz for college, where she studied printmaking and pre-Columbian art history. Even though she didn’t have much of a musical background, she found herself easily falling into the local music scene.

“I just really loved the challenge of saying ‘Let’s create something together,’” she says. “I didn’t know at the time that I would spend the next fifteen years of my life doing it.”

She picked up the bass, started playing with the Muggs, a Santa Cruz punk band with bits of emo and alt-rock in their DNA. One day, the Muggs booked a show at the Whole Earth Café at UCSC, sharing the bill with another Santa Cruz group, the ten-person ska band Slow Gherkin.

At the time, the Santa Cruz scene was teeming. There was Good Riddance and Fury 66, Riff Raff, the Exploding Crustaceans and Soda Pop Fuck You, all with their own take on punk music. Even in such a crowded scene, the Muggs impressed Slow Gherkin.

“We were like who are these guys? Where did they come from? These songs are incredible,” recalls Slow Gherkin singer James Rickman.

Though she hardly knew anything about ska, Osaki struck up a friendship with the band of Santa Cruzans. It was hard not to. They played all around town, ran their own record label (Join Or Die), and brought a buzzing energy with them everywhere they went. There was also this

guy they kept talking about, Mike Park.

“They always talked really highly of Mike,” Osaki remembers. “I was like, ‘Oh my god, there’s an Asian guy that has a record label?’ I had never heard anything like that.”

One day, when they were headed over the hill to visit him, she decided to hop in their van and check it out herself. Soon, they were winding through the Santa Cruz Mountains across Highway 17. On the other side, they pulled up to a garage in the shadow of an old oak tree. There, she met Park, saw the operations at Asian Man (aka the garage), and

offered her services as an employee.

Though Park initially shot her down, the two connected over music. She told him she played bass. He mentioned he was starting an all-Asian American ska band and could use a bass player. They stayed in touch.

But with the label taking off, Park soon realized that there were plenty of things Osaki could do to help—even if he wasn’t sure what exactly they were yet. When he finally asked her to come work at Asian Man, the job offer was typically informal.

“I think it was like, ‘Come on Tuesday.’ And I showed up,” she remembers.

To begin, he put her on an important early task: digging through boxes of unopened zines and scouring them for suitable advertising space.

“It was all mail order, so the only way you knew how to mail order was to get the address from an ad,” Osaki says.

A giant Link 80 logo caps an early Asian Man ad in the Sept 1997 issue of Maximum Rocknroll (MRR 172). The label had just released their second album, the EP Killing Katie (AM-014), which they sold for $6 on CD or 10-inch LP. MU330 and Blue Meanies logos appear next, their split 7-inch (AM-015) advertised for a mere $4. Another ad, from the Dec 2001 issue, introduced the power-pop band the Plus Ones, a four-piece that had been “rocking the bay area scene the last few years.”

This particular ad ends with a note:

“This ad was made w/out a computer. Cut & paste! Took over 2 HRS though!”

The label’s advertising design, Osaki says, “was just like, strips of paper gluesticked onto another piece of paper. We would type it all out and then we would put it on the ad, and then you would put your address.”

The next part still amazes her.

“And then people would send you cash.”

**

‘Elvis Is Dead, I’m Still Alive’ comes out May 19, 2026. Pre-order it from Clash Books.