Now Reading: 10 Nu Metal Albums That Even Nu Metal Skeptics Need To Know

-

01

10 Nu Metal Albums That Even Nu Metal Skeptics Need To Know

10 Nu Metal Albums That Even Nu Metal Skeptics Need To Know

We’re about a quarter-century removed from the days when nu metal ruled the airwaves, and the once-maligned subgenre of music continues to hold a hell of a lot more cultural significance than its critics ever wanted it to. Nu metal’s white-male-dominated aggression had indefensible features like misogyny, homophobia, and cultural appropriation; it had musical traits that understandably turned off the music listeners that lamented the mainstream co-opting of “alternative” music; and it became far too oversaturated with seemingly-interchangeable bands by the dawn of the 2000s. It deserved a lot of the criticism that it got, but it also received a lot of unfair criticism. Nu metal was full of musical innovation that too often got written off because the critics of the time didn’t understand it, and nu metal bands often had powerful subject matter, with songs that took on topics that the mainstream society of the 1990s and early 2000s needed to be more open and honest about. And as much as nu metal was stereotyped as a genre fueled by white male rage, it’s hard not to think that nu metal was often written off because of the way it openly embraced historically-Black styles of music like funk and hip hop.

Today, fond nostalgia and positive re-evaluations for nu metal bands are everywhere you look. One of the most instantly-popular music festivals of the 2020s, Sick New World, is built on it. The recent System Of A Down stadium shows were some of the biggest and most in-demand rock concerts of the year. Deftones seem to be even bigger now than they were then, with younger generations flocking to the band and great new music to back it up. Slipknot were just given the Best New Reissue treatment from Pitchfork, which mostly ignored nu metal during its peak popularity years except to occasionally trash it. With the benefit of hindsight, nu metal is now widely seen as the important, unique moment in music history that these very famous bands’ fanbases always knew it to be.

I’m a firm believer that even the most-maligned subgenres have their undeniably great moments, so I’ve put together a list of 10 classic nu metal albums that even nu metal skeptics need to know. The list ranges from some of the genre’s most foundational albums to some of the most genre-defying, though “genre-defying” is actually sort of a hard qualifier to apply to nu metal because it’s one of the hardest genres to define in the first place. It’s called nu metal but its earliest bands were more directly rooted in alternative rock than in heavy metal. A lot of nu metal bands have rapping and other hip hop elements like turntablism but not all. Some nu metal bands veer towards death and thrash metal while others veer towards industrial. Of the 10 albums on this list, almost all of them sound drastically different from one another. Out of context, it’s not always easy to understand what exactly does tie all 10 of these bands to the same subgenre. But that open-endedness is part of the beauty of nu metal, and it’s part of why it’s so shortsighted to say that all of nu metal is bad. I would say there’s at least one nu metal band for every rock or metal fan of the last 40 years, and if you haven’t already heard all 10 albums on this list, I think some of them might surprise you. I’m mostly a nu metal skeptic-turned-convert myself, and there were points in time when almost all of the albums on this list surprised me.

Read on for the list, in chronological order…

Korn – Korn (1994; Immortal/Epic)

Like Metallica’s debut album for thrash metal and Black Sabbath’s debut album for metal in general, the line between proto-nu metal and nu metal is Korn’s debut album. As this list will continue to touch on, defining the sound of nu metal is not easy to do, but “music that sounds at least a little bit like Korn” is a pretty close catch-all. And as for the artists that we do now consider “proto-nu metal,” Korn were the first band to put a large percentage of them in the same blender.

The roots of nu metal actually lie a little bit more in non-metal than in metal, and Korn’s debut album is a perfect case study of that. Korn did take influence from groove metal bands like early ’90s-era Prong and Sepultura, but they even more so saw themselves as the logical progression of funk-infused bands like the Red Hot Chili Peppers and Faith No More. Referring to the latter’s 1989 album The Real Thing, Korn vocalist Jonathan Davis himself said, that it “showed everybody you could do heavy music and not be ‘metal.’” In a world where Korn weren’t credited with pioneering an eventually-widely-maligned metal subgenre, they might’ve just gone down as one of the many weirdo heavy rock bands that populated ’90s Lollapalooza lineups like Rollins Band, Fishbone, Primus, Tool, Body Count, or Rage Against the Machine. (Korn were actually supposed to play Lollapalooza 1997 but had to cancel due to illness; they eventually played in 2025.) And though the maligning of nu metal caused a lot of those bands’ fans to turn their noses up at Korn over the years, there’s no reason now to think fans of any or all of them wouldn’t like Korn’s first album.

Prior to the formation of Korn, three of its members–guitarist James “Munky” Shaffer, bassist Reginald “Fieldy” Arvizu, and drummer David Silveria–found moderate success as members of the funk metal band L.A.P.D., who cut a 1989 EP and a 1991 album for LA label Triple X Records (Jane’s Addiction, The Vandals, Adolescents, etc). But it wasn’t until after the departure of lead vocalist Richard Morrill that the search for a new vocalist led them to the freakish sounding Jonathan Davis–from a less established band called SexArt–and everything clicked. Along with newly-added second guitarist Brian “Head” Welch, the five-piece band named themselves Korn and started writing songs that were darker and weirder than L.A.P.D., with discordant, groove-based riffs that pushed alternative heavy rock music to even more primal places than it had already gone by 1993. As legend has it, crowds formed around the studio they were recording their ’93 demo Neidermayer’s Mind in just because no one had heard anything like it before.

The riffs and grooves alone were revolutionary, but nu metal wouldn’t have become one of the defining youth movements of the ’90s and 2000s without Jonathan Davis’ lyrics. Davis rejected the howling vocal style that dominated metal by the early ’90s and instead embraced a feverish delivery and a knack for scatting that could easily be traced back to Mike Patton and Anthony Kiedis. He also rejected common heavy metal lyrical themes like horror, war, fantasy, sex, and the occult in favor of deeply, deeply personal lyrics that were more closely tied to the angst-driven grunge movement. He sang about a childhood in which he was bullied, sexually abused, and called homophobic slurs and he did so with a blunt honesty that seemed shocking even in the era of “Jeremy” and “Polly.” His devastating delivery made his subject matter sound even more unsettling than it did on paper, and the last key ingredient of Korn’s disturbing debut album was the caustic, jagged production by the then-little-known Ross Robinson. Korn’s self-titled debut LP was as much a breakthrough for the band as it was for Ross, who went on to become nu metal’s most in-demand producer.

The ’90s was a decade of unfiltered self-expression, and of taboos and underground cultures infiltrating the mainstream, and Korn played a massive role in all of that. This album has spoken to generation after generation of misfit kids for the 30+ years it’s existed, and it sent shockwaves through the music world that led to such an influx of similarly strange, heavy bands that an entire new subgenre was coined in its wake. For the uninitiated, I have just three more words: Are you ready?

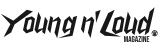

Sepultura – Roots (1996; Roadrunner)

As nu metal quickly became a sensation, some of the bands that influenced it turned their noses up at it, others embraced it, but none of those bands went on to make a straight-up nu metal album of their own the way Sepultura did. Their own transformation from thrash/death metal to groove metal on 1993’s Chaos A.D. inspired the ensuing nu metal boom, and in turn, Sepultura were blown away by Korn’s debut album and another rising nu metal band that were associated with Korn early on, Deftones. Wanting to get a similarly raw sound for Roots, they got in the studio with Korn producer Ross Robinson (who also produced one track on Deftones’ 1995 debut album Adrenaline), and they brought in Korn’s Jonathan Davis to assist them on the song “Lookaway.” That song also features fellow proto-nu metal pioneer Mike Patton of Faith No More and Mr. Bungle, and it embraced nu metal’s hip hop influences with scratches from House of Pain’s DJ Lethal, right around the same time that Lethal joined the soon-to-be-gigantic nu metal band Limp Bizkit. While also continuing to explore the Brazilian folk music influences that populated Chaos A.D., Sepultura took this exciting then-new offshoot of metal and helped push it forward. At times, the Korn influence was obvious. And at other times, the combination of the downtuned murky guitars, Max Cavalera’s throat-shredding barks, and Igor Cavalera’s manic drumming sounds like proto-Slipknot. Roots remains one of the most crucial examples in heavy music history of a veteran band seeing the tides turning towards something new and finding ways to actually contribute to the new thing, a feat that was especially difficult in the ’90s when Alternative Nation was making so many ’80s metal bands instantly look like dinosaurs.

Roots would be the last Sepultura album with Max Cavalera, who was replaced by new vocalist Derrick Green on 1998’s Against, but it wasn’t the end of Max’s nu metal journey. He went on to form the nu metal band Soulfly, whose early records included collaborations with Fred Durst, Chino Moreno, and Corey Taylor, and one of those albums could’ve ended up on this list too (but I decided that keeping it to one album per band also meant one album from Max Cavalera). By the time nu metal peaked in popularity with Soulfly as one of the genre’s core bands, Max had solidified himself as a musician who was just as important to nu metal as he was to thrash, groove, and death metal before that. And it all started with Roots.

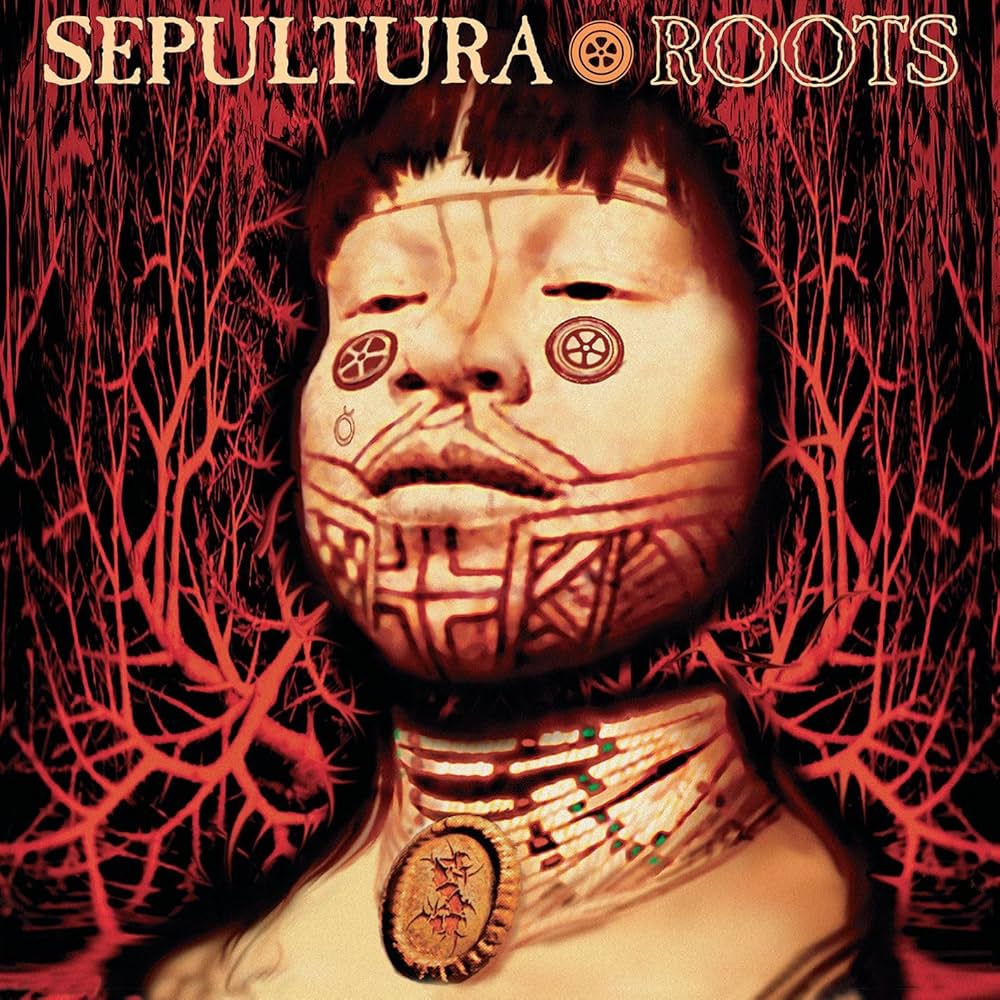

Incubus – S.C.I.E.N.C.E. (1997; Immortal/Epic)

Of all the “they used to be a nu metal band?” bands, none had a better nu metal period than Incubus. (Sorry, Sugar Ray.) They started out worshipping at the funk metal altar of bands like the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Faith No More, Mr. Bungle, and Primus, and after signing to Epic/Immortal (thanks to the same A&R who signed Korn), they expanded their lineup to include turntablist DJ Lyfe, whose hip hop-inspired record scratches clashed with Mike Einziger’s monster riffs, Dirk Lance’s funk basslines, and Brandon Boyd’s Kiedis-meets-Patton vocal workouts to create a fresh new racket that fit right in with the then-burgeoning nu metal movement. (And shoutout to drummer José Pasillas, who held it all down with his ability to niftily move between metal, funk, and hip hop.) It all came together on Incubus’ 1997 major label debut S.C.I.E.N.C.E., an album that somehow wears its influences on its sleeves yet sounds like nothing else released before or since… including by Incubus. After this album, Incubus toned down the funk elements, and though they’ve got a handful of other monster riffs on later albums (“Nice to Know You,” “Megalomaniac,” and “Sick Sad Little World,” to name three), they were never as all-out heavy as they were on S.C.I.E.N.C.E.. When this album goes full headbanger mode, it’s easy to see why Incubus toured with Korn and System Of A Down and played Ozzfest surrounding its release. It’s also easy to see why and how Incubus pivoted towards cleaner alternative rock on S.C.I.E.N.C.E.‘s 1999 followup Make Yourself and never looked back. As much as Brandon Boyd had the shouted delivery needed for nu metal, even on this album he had the soaring singing voice needed for all of Incubus’ later breakout hits. And that’s a big part of what makes S.C.I.E.N.C.E. so special; it presents a generationally iconic singer in an environment that none of his most popular albums find him in. It’s like hearing Jay-Z on Reasonable Doubt, or (past Incubus tourmates) Jimmy Eat World on Clarity. No matter how many times you listen to albums like these, you still feel like you’re peeking at buried treasure.

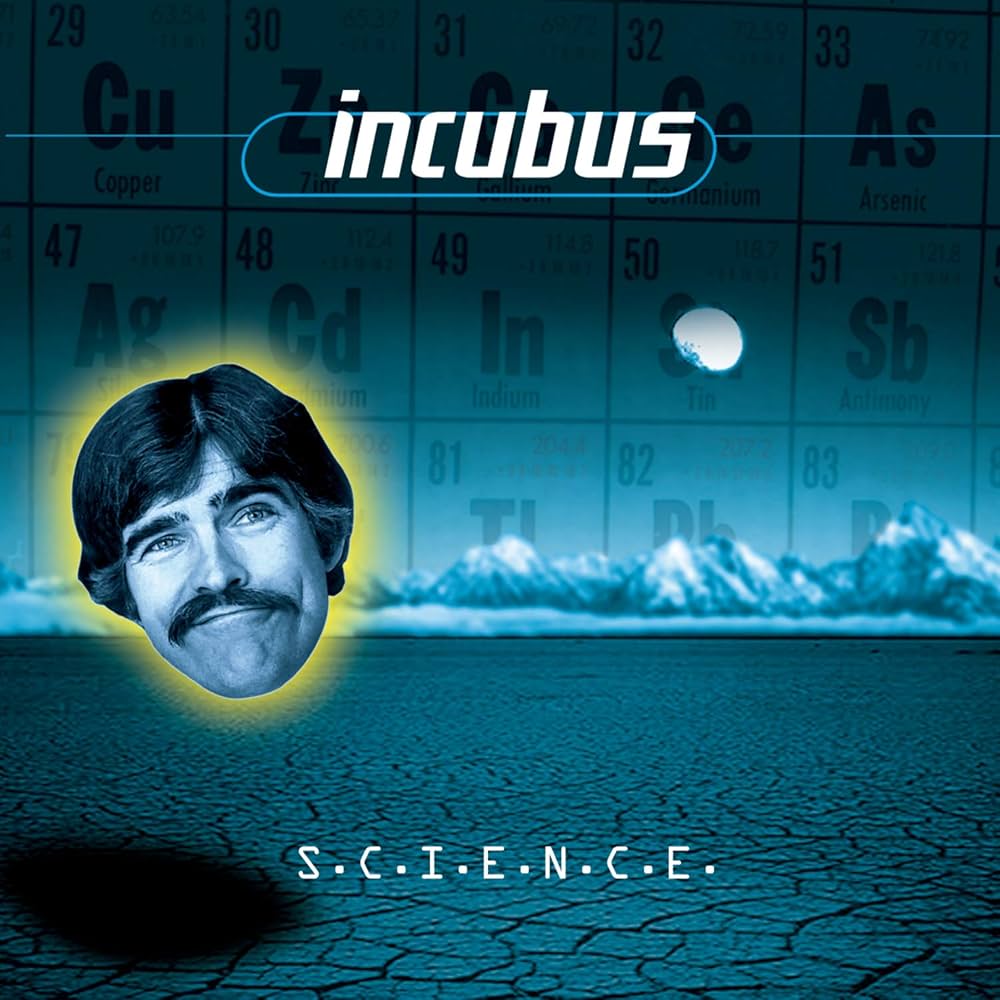

Slipknot – Slipknot (1999; Roadrunner)

By the end of the 1990s, nu metal had become stereotyped as the mall-friendly rebel music for suburban white guys with nothing to rebel against. It was seen as music that borrowed the violence and misogyny of hip hop but stripped away its societal context, and a watered-down bastardization of heavy metal that aimed its aggression at nothing in particular. Its cultural milemarker was Woodstock ’99, where acts like Limp Bizkit and Kid Rock put on notorious sets that did nothing to fight back against the stigma that nu metal had developed.

About a month before that festival, a group of nine freaks emerged out of the cornfields of Iowa with a new take on nu metal, and they called themselves Slipknot. As nu metal was becoming increasingly commercial, Slipknot looked to thrash and death metal and they put a much darker, heavier twist on metal’s nu-est subgenre. They did have a turntablist, but they never veered into whitewashed rap-rock. They all wore nightmarish masks and they had a member named Clown who bangs on trash cans. The world had never seen anything like it.

The summer of ’99 introduction to Slipknot that I’m speaking of is their self-titled debut album, though the band actually formed four years earlier and self-released an album (1996’s Mate. Feed. Kill. Repeat.) with a different singer (Anders Colsefni) before recruiting Corey Taylor and turning Slipknot into the band we know and love. After a demo of the song “Spit It Out” caught the attention of Korn producer Ross Robinson, Slipknot signed to Roadrunner, hit the studio with Ross, and came out with one of the most pivotal debut albums in nu metal history. Right from the thunderous drums that introduce “(sic),” you know you’re listening to something extreme not just for nu metal standards but for metal in general. From there, you get the industrial breakbeats of “Eyeless,” the apocalyptic discordance of “Tattered & Torn,” the mosh-fuel riffs of “Liberate,” and in general just a relentless onslaught of heavy music that’s scary enough to match Slipknot’s masked exterior. The guitars are nasty, the percussion is pure madness (rest in peace to the legendary Joey Jordison), and Corey Taylor knew how to deliver his harsh screams in a way the mainstream could latch onto. On “Wait and Bleed,” he also shows off a knack for catchy clean-sung choruses that he’d take to way higher heights a few years later on hit songs like “Duality” and “Before I Forget,” and even when Slipknot did embrace their pop aspirations, they still sounded far more extreme than just about any band that got as much MTV time as they did.

Kittie – Spit (2000; Artemis)

Nu metal faced a lot of deserved criticism for being too much of a testosterone-fueled boys’ club, but there were bands that challenged that, like the Canadian quartet Kittie, who brought some riot grrrl energy to the nu metal scene with their 2000 debut album Spit. Songs like “Do You Think I’m a Whore?,” “Paperdoll,” and “Choke” made for a necessary antidote to “Nookie,” “K@#Ø%!,” and “All In The Family,” and outside of their lyrical content, they also brought a raw energy to Spit that counteracted the polished sound of so many nu metal hits. Like Slipknot (who Kittie toured with right after the album came out), they had a clear interest in underground extreme metal, and they fused that with the downtuned grooves of Korn and Deftones as well as the haunting melodies of grunge bands they loved like Nirvana, Hole, Soundgarden, and Alice In Chains. Spit is produced more like a hardcore record than a mainstream metal record, and Morgan Lander’s screams on this LP are filled with raw aggression. And just as remarkable as her screams is her ability to go from a throat-shredding roar to a post-grunge warble at the drop of a hat. From her wide vocal range to the band’s casually genre-defying approach (that also dipped its toes into electronic music with the breakbeats on “Brackish”), Spit still stands out as a nu metal artifact like few others.

Deftones – White Pony (2000; Maverick)

It’s hard to pick just one album for a lot of the bands on this list, but it’s especially hard for Deftones. More so than any other band here, they’re making some of their best music right now, and they’ve evolved so much that it’s hard to represent them with just one album. You might argue that their 1995 debut album Adrenaline–written around the time they were frequently playing shows with Korn–is their most nu metal album. You also might argue that White Pony isn’t really a nu metal album at all. But if pressed, White Pony still feels to me like the most definitive Deftones album, and I also think the things that make it “not really nu metal” are also the things that make it extremely nu metal. With elements of trip hop, shoegaze, electronic music, post-rock, and other atmospheric subgenres, it’s kind of the nu metal counterpart to Radiohead’s Kid A, which was released that same year. Chino Moreno adopts a dream-poppy coo throughout the album, but White Pony also has shout-rapping, turntablism, Headbangers Ball riffs, and other distinctly-nu-metal traits. Its one guest feature comes from another artist who always existed on the fringes of mainstream alt-metal, Tool’s Maynard James Keenan, and there are definitely some similarities between what Deftones did on White Pony and what Tool did on the following year’s Lateralus. White Pony is an album that entirely transcends not just nu metal but metal in general, and its genre-defying traits are also what makes it feel like such a part of the nu metal story. Nu metal wasn’t just about sounding like Korn; it was about pushing limits.

Mudvayne – L.D. 50 (2000; Epic)

Because Mudvayne wore creepy facepaint and Clown from Slipknot took them under his wing–co-executive-producing their 2000 debut album L.D. 50 and taking them on tour that same year–the comparisons to Slipknot were inevitable, and there’s no denying that the album’s breakout single “Dig” sounded more than a little like Slipknot. But the more you (ahem) dig into L.D. 50, the more you find a timeless nu metal album with layers and layers of depth. “Dig” is a balls-to-the-wall nu metal rager, and it’s far from the only time that L.D. 50 turns it up to 11. But in between all the rage, there’s excursions into progressive rock, jazz fusion, funk metal, abstract hip hop, and sci-fi soundtrack interludes. The instrumentation favors trippy atmospherics about as much as it favors mosh riffs, and singer Chad Gray balances out his throat-shredding screams and shouts with a Maynard James Keenan-esque croon. As the album veers off into melodically surreal territory, it’s not hard to hear why Mudvayne have cited bands like King Crimson, Rush, and Genesis as core influences over the years. The eye-catching facepaint and the banger single were just the tip of the iceberg; the other 65 minutes of L.D. 50 had so much interesting, unpredictable stuff stirring beneath the surface.

American Head Charge – The War of Art (2001; American)

American Head Charge caught the attention of System Of A Down bassist Shavo Odadjian after AHC opened an Iowa show for SOAD in 1999, and Shavo then showed the band to SOAD’s producer/American Recordings label head Rick Rubin, who was also impressed. Rick signed them to American and co-produced their breakthrough album The War of Art, which he then released just one week before System Of A Down’s Toxicity (more on that one soon). And listening to this album, it’s not hard to hear why a member of System Of A Down was impressed. They weren’t as over-the-top political as SOAD, but they definitely worked some critique of America in the LP, and they eschewed nu metal’s campier elements in favor of music that just hit hard. They were often compared to Ministry (who they released a cover of the year before this album came out), and AHC knew just how to revamp that band’s heart-pounding industrial metal for a new (or nu) generation. Sadly, struggles with addiction and mental illness forced the band into hiatus not long after the album’s release, and they ended up parting ways with Rick Rubin and American Recordings before releasing their lesser-known 2005 album The Feeding, which came out two months before guitarist Bryan Ottoson died of a drug overdose at age 27. (Just this week, the news broke that frontman Cameron Heacock has been homeless for years.) After leaving American, The War of Art faded into obscurity (it’s in desperate need of a reissue and it’s not currently on streaming services), but you didn’t have to be there to understand what a nu metal gem this is. It holds up as some of the hardest-hitting music of its era.

System Of A Down – Toxicity (2001; American/Columbia)

Nu metal’s stereotype as a vessel for aimless American white male rage never described System Of A Down. The band, made up of four members of the Armenian diaspora, used their 2001 magnum opus Toxicity to address America’s prison system, the war on drugs, drug abuse, police brutality, and the 1915-1917 Armenian genocide that vocalist Serj Tankian’s own grandparents survived. (They also provided commentary on Hollywood stereotypes, in both their lyrics and with the album cover.) And they communicated their messages through music that was genuinely innovative. What SOAD did share with other nu metal bands was a chunky, groove-forward approach that eschewed the flashy guitar work of traditional heavy metal, but they had a unique take on the genre that none of their peers shared. Toxicity owes as much to the simplicity and intensity of hardcore punk as it does to crooned balladry, and it channels the shape-shifting chaos of ’70s progressive rock into the blunt force of ’90s alternative rock and metal. (As with many nu metal bands, Faith No More and Mr. Bungle seemed like a clear influence, but no nu metal singer gave Mike Patton’s pure and utter weirdness a run for its money like Serj.) Toxicity incorporates the sounds and melodies of Armenian and Middle Eastern folk music, and SOAD augment metal’s typical guitar/bass/drums formula with sitar, string arrangements, chanting, and more. As a vocalist, Serj can switch from an operatic howl to a throat-shredding scream on a dime, and the approach to melody that he and guitarist/backing vocalist Daron Malakian brought to the band was unlike anything else happening in mainstream American music at the time (or since). Their sense of rhythm and song structure was just as atypical as their melodies, with songs that would stop and restart on a whim and drastically change tone mid-verse. And no matter how weird or aggressive SOAD got, they always knew how to write a chorus you could sing along to. Just walk into any room where someone’s blasting “Aerials,” “Toxicity,” or especially “Chop Suey!” and you’ll find metalheads and non-metalheads alike yelling every word.

For more on this album, read our full 20th anniversary review.

Linkin Park – Meteora (2003; Warner)

The logical and inevitable conclusion of nu metal’s immersion into the TRL-friendly mainstream pop music was Linkin Park’s 2000 debut album Hybrid Theory. In Chester Bennington, they had a nu metal singer who could really sing–even when he screamed, he could carry a tune like any Max Martin-produced pop star. His counterpart was rapper Mike Shinoda, whose nursery-rhyme bars were likely influenced by Linkin Park collaborators like Black Thought and Pharoahe Monch but easier for suburban America to digest. Beneath the two vocalists was a mixture of metal, industrial, electronic music, and hip hop that was innovative but accessible, with slick production that made even the heaviest moments easy on non-metalhead ears.

Hybrid Theory turned Linkin Park into stars, and with increased fame and power, they had the freedom to experiment a little more with their next album and spend about twice as much time recording it. The result was Meteora, an album that doubled down on the best aspects of Hybrid Theory while simultaneously hinting at the departure from nu metal that they’d make on 2007’s Minutes to Midnight. As pivotal and important as Hybrid Theory is, the Linkin Park of Meteora is stronger, more confident, and just simply better.

On Meteora, Linkin Park’s vast array of influences came together even more seamlessly than they did on Hybrid Theory. “Breaking the Habit” is basically an electronica/trip-hop song with no elements of metal at all, “Nobody’s Listening” is a straight-up rap song with a Japanese flute loop, “Hit the Floor” is aggro mosh fuel, and all of those different-style songs sound like parts of the same whole. After going for instant satisfaction on all of Hybrid Theory‘s singles, Meteora lead single “Somewhere I Belong” has a multi-layered, 40-second build-up before vocals even come in. Moments like the reverse guitar in “Somewhere I Belong” and the string loops and breakbeats in “Faint” revealed an album as meticulously crafted as forebears like The Downward Spiral and White Pony. And Linkin Park’s artistically explorative process did nothing to hurt their commercial impact; “Faint,” “Somewhere I Belong,” “Breaking the Habit” and especially album closer “Numb” became just as omnipresent as the Hybrid Theory singles.

Just like on Hybrid Theory, the slick production and the pop-friendly choruses could almost mask the open wounds in Chester’s lyricism, wounds that have continued to hit even harder after the singer took his own life in 2017. It’s just as easy to yell along to hooks like “I wanna let go of the pain I’ve held so long” and “Time won’t heal this damage anymore” and not really think about what you’re yelling along to as it is to find solace in these songs when you need it most. Just like Korn’s debut had done nearly a decade earlier, Meteora spoke to a new generation of nu metal listeners about the pain, loneliness, and depression that too often gets bottled up or ignored. The music sounded like an entirely different version of nu metal than the one that Korn helped invent, but the emotional impact was the same.

FURTHER READING

* System Of A Down and Korn at MetLife Stadium – 8/28/2025 Live Review

* Deftones – Private Music Album Review

* Slipknot Celebrated 25th Anniversary of S/T LP at Madison Square Garden – Live Review

* 15 Seminal Albums from Metalcore’s Second Wave (2000-2010)

**